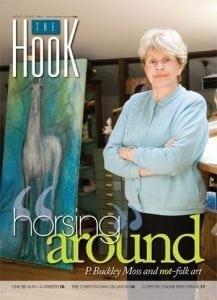

COVER- Horsing around: P. Buckley Moss and not-folk art

Crowd control

Now nearly 74, when Moss returns to Waynesboro it’s usually a working trip to take care of business at the P. Buckley Moss Museum– home of her original paintings– which opened in 1989 off Interstate 64. Even her home in the Barn turns into a workplace of sorts. It has a velvet rope through the living room for crowd control when Moss collectors and fans line up to get her autograph. And there are other measures designed to keep the line of fans moving.

“They aren’t allowed to talk to me,” says Moss, “but I talk to them. And I get two bathroom breaks.”

It’s also usually for business that she goes to her house in Chesapeake, where the Moss Portfolio publishing and distribution center is. “I come in for an hour, and I’m there four hours,” she says.

Hence the appeal of Florida. She can paint, the light is great, and there’s no Buckley-mania.

“My friends in Florida are all filthy rich,” she says. “They don’t care how much money I have or what I do. I don’t want people knocking on my door everyday. If they do, I tell them I’m the maid. And I look like the maid, not someone who owns this multimillion-dollar property.”

She also owns two houses in Italy, where she likes to do etchings. “At one time I had 15 properties– can you believe it?”

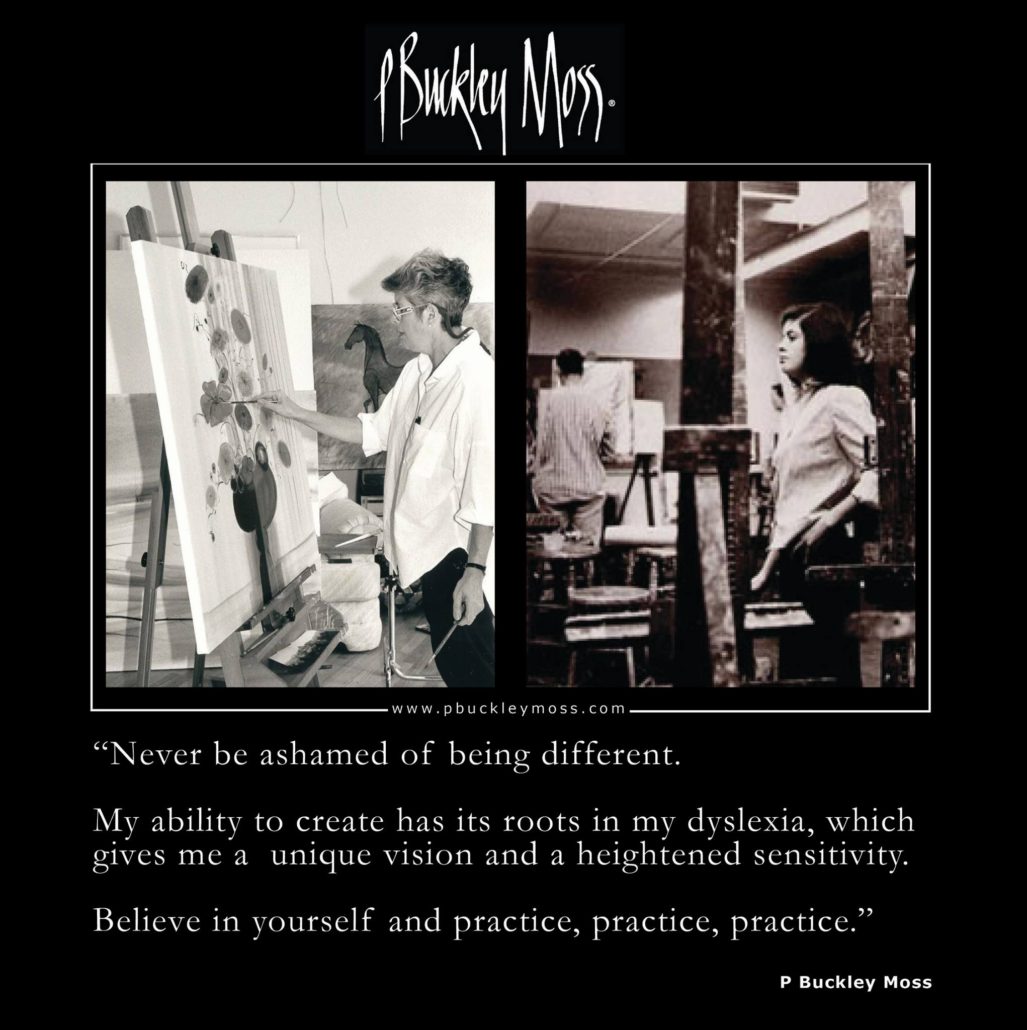

Harder to believe is this– a dyslexic girl from Staten Island grew up to launch one of the most successful art careers today– from Waynesboro– and it’s not all about the Amish and footless geese.

Portrait of the artist as a young girl

“I liked to be Tarzan,” recalls the former Patricia Buckley. One day when she was swinging alone on a rope swing, the line broke. “I landed in the dirt, and I was knocked out for a long time.” Another time she broke her arm sliding down a New York fire escape.

Tomboyish athleticism came more easily to her than success in the classroom, but she didn’t find out she was dyslexic until she was an adult. Fortunately for the young Pat, a nun realized there was an artistic young woman in their midst, and her mother got her into the Washington Irving High School for the Fine Arts in Manhattan. From there she went to art school at the Cooper Union on a full scholarship.

“I was very lucky,” she says.

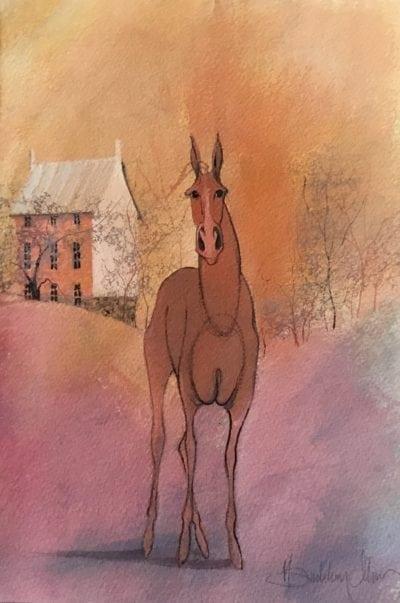

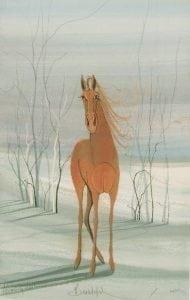

Early on, before ever seeing the Shenandoah Valley that she became famous for portraying, she was painting horses. And religious images.

“My daughter does so many of these goddamn crucifixions. I don’t know what’s wrong with her,” Moss quotes her mother as saying. Elizabeth Buckley, a Sicilian American, had been a dress designer and worked as a tour guide at her daughter’s museum before she died nearly six years ago at age 97.

Moss chuckles at the memory of her mother who “just wanted to get a rise” out of museum visitors.

P. Buckley Moss settled on her professional moniker early on. “Women were not respected when I was in school,” she says. “Men got all the scholarships, the Fulbrights. So I said I’d be a man.”

After the Cooper Union, she married Jack Moss and had six kids in nine years. So how did she paint?

“I stayed home,” she replies. “I worked a lot at night, and still do.” And in 1981, after she renovated the Barn (it’s now surrounded by a Waynesboro subdivision), she built a cottage next door for her children so she could continue burning the midnight oil without putting up walls.

A 1966 painting, “Madonna,” is a self-portrait of a serious, dark-haired young woman holding a blond infant– Christopher, her youngest, who was born that year. She looks tired.

Valley girl

Unlike most New Yorkers who migrate to Virginia, Moss doesn’t confess any culture shock, perhaps because when you have six kids, you’re in a different kind of shock. But one image took root.

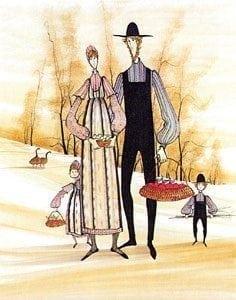

She was familiar with the Amish in Pennsylvania, and in 1967, after her introduction to the local Mennonite and Amish communities in Waynesboro, she began her “plain people” series.

Over the years, the plain people, who eschew modern machines and value modesty, have become part of the Moss iconography.

“They thank me for depicting them in a way that is wholesome,” she says.

In 1978, Moss met Malcolm Henderson, who became her business manager and second husband.

“Malcolm was a marketing genius,” says Peter Rippe, director of the P. Buckley Moss Museum from 1989 to 2000. “Malcolm Henderson had a lot to do with moving her from a sidewalk artist to a gallery artist.”

Rippe recounts a story about their first meeting, when Henderson had a gallery in Georgetown and displayed in the window a Moss painting he’d gotten from a client.

Someone told Moss about it, and she was mystified because she knew she hadn’t given it to the gallery to sell. She came in and demanded, “Where did that come from?”

“One of my customers was trading up,” Henderson answered, according to Rippe, who laughs.

Henderson insisted that Moss screen her dealers and use the best reproductive techniques, printers, and paper, Rippe says. “He was a stickler for fine framing.”

Perhaps more importantly, Moss’s art is accessible, and that serves a function, says Second Street Gallery director Leah Stoddard. “She offers people the opportunity to put something on the wall other than a Monet poster.”

But Stoddard says she would not try to mount a Moss show at Second Street, which features emerging artists on the way to regional or national recognition.

“Her work is not considered by critics as groundbreaking,” says Stoddard. “It has not tended to push the envelope. It’s more decorative in nature and about design. The pioneering spirit isn’t there for me as a curator.”

Stoddard doesn’t mind an artist with a marketing machine, but she cautions, “People may buy a P. Buckley Moss print for $1,000 and think it’s really worth that.”

She compares mechanically mass-produced prints– “Some of her runs are in the hundreds, and that could be problematic”– to the dying art of hand-pulled prints done by a master printer and the artist in runs of, say, 30.

On the website prints.com, the hundred or so Mosses run from an 8.5-inch print of “Early Christmas Morning” for $49.99 to the nearly 21-inch wide “The Doctor’s Office” for $809.95.

“Collectors get confused about what is valuable when they can have hand-pulled prints for less,” says Stoddard. “In this town, you can buy an original work for under $200.”

That logic is unlikely to dissuade P. Buckley Moss fans, who may eye fancy-pants Charlottesville art galleries with suspicion. And Moss herself isn’t keen on going to Charlottesville. “It’s too crowded,” she says.

People’s artist

When she was in school, Moss admired “all the people you’d suppose who work hard.” By that she means El Greco, Modigliani, and Picasso– although she offers a stipulation with Picasso.

“I wouldn’t hang his work,” she says. “He wasn’t a nice person. He was a bastard, but I admire what he accomplished.”

She also confesses a fondness for Michelangelo: “I love David’s rear end in Florence. He has the best buns.”

Moss may not do sculpture, but her subject matter and style go far beyond the plain people and pastels that many associate with her work.

“Pat is a formally trained artist,” says Malcolm Henderson’s son, Jake, president of P. Buckley Moss Galleries Ltd. “You can see where her work has a very solid art background.”

“It’s not folk art,” says Moss. “It is a realistic form of stylized impressions. It starts with an abstract concept, and I make it more understandable.”

She mentions her blue flowers, which are more Matisse than Grandma Moses, and she’s done cubist crucifixions.

So what’s with the footless geese?

“In the Bible, feet are a sign of pride,” says Moss before she refers the question to Bonnie Stump, curator of the P. Buckley Moss Museum, who’s written a guide to the symbolism and iconography in Moss’s art.

“She paints them without feet because in the Renaissance, the devil [was depicted with] webbed feet,” explains Stump. “She didn’t want that on her divine creatures.” Geese, for Moss, are symbols of divine providence, loyalty, and matrimony.

Stump makes a more practical observation– a lot of times the birds are standing in snow, in water, in grassy fields, or in the sand on beaches, so you wouldn’t see their feet anyway.

Why is Moss so popular?

Jake Henderson points to her ability to paint a broad number of subjects in a broad number of styles– landscapes, architecture, animals. Abstract, expressionistic, realistic.. to a degree.

“Her style makes her work collectible,” says Henderson. “And it’s not available on every street corner.”

He adds that the variety also appeals to a large number of people. “And because she’s always trying something new, it keeps her work fresh.”

Her employees also note that Moss is a workhorse. “She paints all the time,” says Henderson. “She crisscrosses the country and brings new people into the galleries– the next generation of collectors.”

Backing her in that marketing effort is the P. Buckley Moss Galleries. “We’re in this business to promote Pat’s career, maintain her stature as a top artist, and maintain the value of her work for her collectors,” says Henderson.

Moss’s successful promotion of her art calls to mind another art marketing machine. But Rippe, who wrote a book about Moss called Painting the Joy of the Soul, doesn’t think “painter of light” Thomas Kinkade’s marketing– or art– is really comparable.

Kinkade runs ads in popular magazines and newspapers and has Franklin Mint editions of his work. “Pat has had her art handled by dealers,” says Rippe. “Certainly she has not advertised the way Thomas Kinkade has.”

Nor has she accumulated lawsuits from disgruntled dealers. Kinkade has been sued by gallery owners, including one in Charlottesville, for deep discounting of his prints on QVC and at a chain store called Tuesday Morning.

Rippe sees major differences between the popular artists. Even though both do lighthouses and vernacular buildings, Rippe compares Kinkade’s style to the romanticism of the 19th-century’s Hudson River School. “He’s so romantic in his approach that he becomes sticky… If you take romanticism to an extreme, you have Thomas Kinkade.”

While acknowledging that Moss can be sentimental, Rippe says, “She’s closer to a medieval illumination. She works basically from a religious platform. She uses line and color as a medieval illuminator. She illuminates with meaning, not light. Not that Pat would ever say that.”

What Kinkade and Moss do share: “People are looking for something they can understand in their art,” says Rippe. “She paints for the people.”

The Amish, her fading horizon lines and soft colors have an appeal. “People seem to enjoy her art, and they enjoy it on a simple level,” says Rippe. “It’s a very decorative style and can be recognized by anyone.”

With recognition have come some critics who use words like “stick people” and “pandering” to refer to Moss’s work.

“A stick figure in terms of iconography reminds people of a deeper meaning,” contends Rippe, “and the Amish are symbols of a type. An Amish man and woman on skates conjure up images in the mind.”

And when critics attack Moss for her simplicity, Rippe suggests they go deeper and consider the iconographic meanings.

“Some of her most significant pieces come from early in her career when she painted more in academic styles,” says Rippe. He mentions an art project from the Cooper Union, Thomas Aquinas’s Book of Man, for which she made the paper, illustrated in gold leaf, and did the calligraphy. It’s now on display at the museum.

“The same thing is in some of her landscapes, the mystery of a winter day, the silence of a winter day, where you can’t figure out where the horizon line is,” says Rippe.

“At times, when she overworks a theme– the Amish theme– it almost becomes…” Rippe hesitates. “I don’t want to say… trite.”

Despite this observation, Rippe points out that for a modest amount, it’s possible to own a piece of her art or a good reproduction. He recalls walking around a tony West End neighborhood in Richmond. “It was amazing the number of her pieces hanging in living rooms over the fireplace…. the Amish skaters.”

Rippe concedes the Amish skaters are not his favorites, and speculates they’re “not hers, either. In her home are hung the pieces with silence and mystery.”

And Moss has her own theory about her popularity.

“I think it’s a communication,” says Moss. “It’s a value thing. I love these lines. I love what I do.” And so do her employees.

Now offered in 400 galleries around the country, Moss’s work generates $10 to $15 million a year and keeps 30 people employed, the president of her company estimates.

Home again

Charmed by the black contour of a bird in a photograph she shows to a visitor, Moss says she incorporated the image into her painting commemorating Jamestown when “all they wanted was three ships.”

Besides maintaining P. Buckley Moss Galleries Ltd., Moss is a major philanthropic force with her art. She’s donated her works to WVPT for decades to raise money for the station.

The P. Buckley Moss Foundation was created in Moss’s honor to support dyslexic and learning-disabled children by promoting art in the schools.

“She’s convinced art is what saved her with her dyslexia,” says Jake Henderson. And when school budgets are slashed, art in the classroom is one of the first things to go.

So how does she combine being a philanthropist with her art empire, as well as the six children and 10 grandchildren, at an age when many would be scaling back their activities?

“You do the things that suit you,” Moss says, “that you care about. I don’t want kids to have a hard time learning. I had a hard time learning.”

And she credits others who help her to help. If someone gives her a watering can, “I’ll decorate it and it’ll go for a couple of hundred dollars,” she says. “I do my thing, they do theirs.”

More than anything, Pat Moss is successful in doing her thing. “I don’t fit in anywhere,” she says, but she’s adored by fans all over the country.

“I’m sorry I don’t have a dark side,” says Moss. “I’ve had lots of bad things happen.”

She stands outside the Barn under a cherry tree where weeds are coming up and shares a couple of juicy stories that, regrettably, are off the record. “It’s not perfect,” she says of the tree– or is she referring to her life?– “I love it.”

And the woman who once felt her art wasn’t taken seriously because of her gender has the last laugh.

“I can do what I want,” she says.

Pat Moss puts visitors in a cottage so she can work at night rather than put up walls inside the Barn.

PHOTO BY BILLY HUNT

Her dyslexia kept her from reading music, so Pat Moss is self-taught– but she doesn’t sound like it when she plays her Steinway.

PHOTO BY BILLY HUNT

The P. Buckley Moss Museum in Waynesboro is a repository of her oeuvre and a mecca for Moss aficionados.

PHOTO BY BILLY HUNT

Source: http://www.readthehook.com/85713/cover-horsing-around-p-buckley-moss-and-not-folk-art

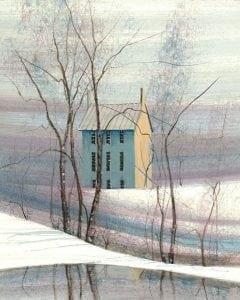

The Moravian Style House, also called the generic house or spirit house, is based on the German style houses from the Moravian period of 1741 to 1844. The Moravian community was founded in Pennsylvania to form a kind of utopia which attempted to bring Christianity to Native Americans while still allowing for cultural expression. Their communal way of life established extraordinary 18th-century industry and hand made crafts which came about through shared cooperative efforts. The Moravian style houses and other communal buildings, including churches, were combined with 18th-century German style architectural elements. These included the use of herringbone pattern doors, high pitched roofs with flared eaves, brick jack-arched windows and doors, tiled roofs, sloping-roofed dormers, and parged stone walls. The deep-set windows represent the largest collection of Germanic style architecture in the United States.

The Moravian Style House, also called the generic house or spirit house, is based on the German style houses from the Moravian period of 1741 to 1844. The Moravian community was founded in Pennsylvania to form a kind of utopia which attempted to bring Christianity to Native Americans while still allowing for cultural expression. Their communal way of life established extraordinary 18th-century industry and hand made crafts which came about through shared cooperative efforts. The Moravian style houses and other communal buildings, including churches, were combined with 18th-century German style architectural elements. These included the use of herringbone pattern doors, high pitched roofs with flared eaves, brick jack-arched windows and doors, tiled roofs, sloping-roofed dormers, and parged stone walls. The deep-set windows represent the largest collection of Germanic style architecture in the United States. Eggs in Moss art signify new life or resurrection. Eggs in art history are often used as symbols of fertility.

Eggs in Moss art signify new life or resurrection. Eggs in art history are often used as symbols of fertility.

Pat Moss comes to the door of the Barn– her house in Waynesboro– and wonders who the heck is standing on her doorstep. She’s forgotten that she has an interview scheduled this morning, but she quickly takes the interruption in stride and seats her visitors in her huge living room in a former apple packing barn.

Pat Moss comes to the door of the Barn– her house in Waynesboro– and wonders who the heck is standing on her doorstep. She’s forgotten that she has an interview scheduled this morning, but she quickly takes the interruption in stride and seats her visitors in her huge living room in a former apple packing barn.

“I did something when so many told me I wouldn’t amount to anything,” said P. (Patricia) Buckley Moss, a name painter based in Blacksburg, Va. “I am still doing and never gonna stop.”

“I did something when so many told me I wouldn’t amount to anything,” said P. (Patricia) Buckley Moss, a name painter based in Blacksburg, Va. “I am still doing and never gonna stop.”